BY CAROLYN LaWELL (and MATT LaWELL)

TACOMA, Washington | Rain falls, of course, and we sit under cover, near the top row behind home plate at Cheney Stadium. Matt hands me a Herb Score Card, photocopied hours earlier at a local mailing center, and I realize I can no longer resist the inevitable.

I have to learn how to score a game.

I danced for 15 years and was raised in ballet. My mother still watches more baseball than I do, probably even during this road trip of a season. I could not care less about trying to fit letters and numbers and slashes inside little boxes. Matt scores games all the time, and it looks like a game in itself, the kind you can never win. But he enjoys it, and he wants to teach me. This can be something we share.

I could not care less about trying to fit letters and numbers and slashes inside little boxes.

(Because what else do you share with the woman you love, other than cramming microscopic shorthand on a sheet of paper for three hours? To have a beautiful card, you have to be at least a little obsessive and a little compulsive. I am. Carolyn is not.)

I look out at the field, still covered with a tarp, and picture the plays the Tacoma Rainiers and Tucson Padres might turn after the skies close again. What are all the numerical values again? First base is 1, right? (No.) Is shortstop 3 or 5? (Neither.) What number is the pitcher again? (What have I gotten myself into?)

I realize my first mistake before the first pitch. I should have written down some of the information Matt passed along while we waited for the gates to open. Then I pull out a black pen. That was my second mistake. (Because you should use pencils. Especially for your first game.)

♦ ♦ ♦

The game starts 46 minutes late after a rain delay, just our second during our first seven weeks on the road, which is sort of incredible. (Also incredible is the fact that we finally arrived in the Pacific Northwest and the whole region complied with all the meteorological stereotypes. Rain is the natural enemy of baseball and the mortal enemy of keeping score. You have to keep your cards dry. Ever try to write on wet paper?)

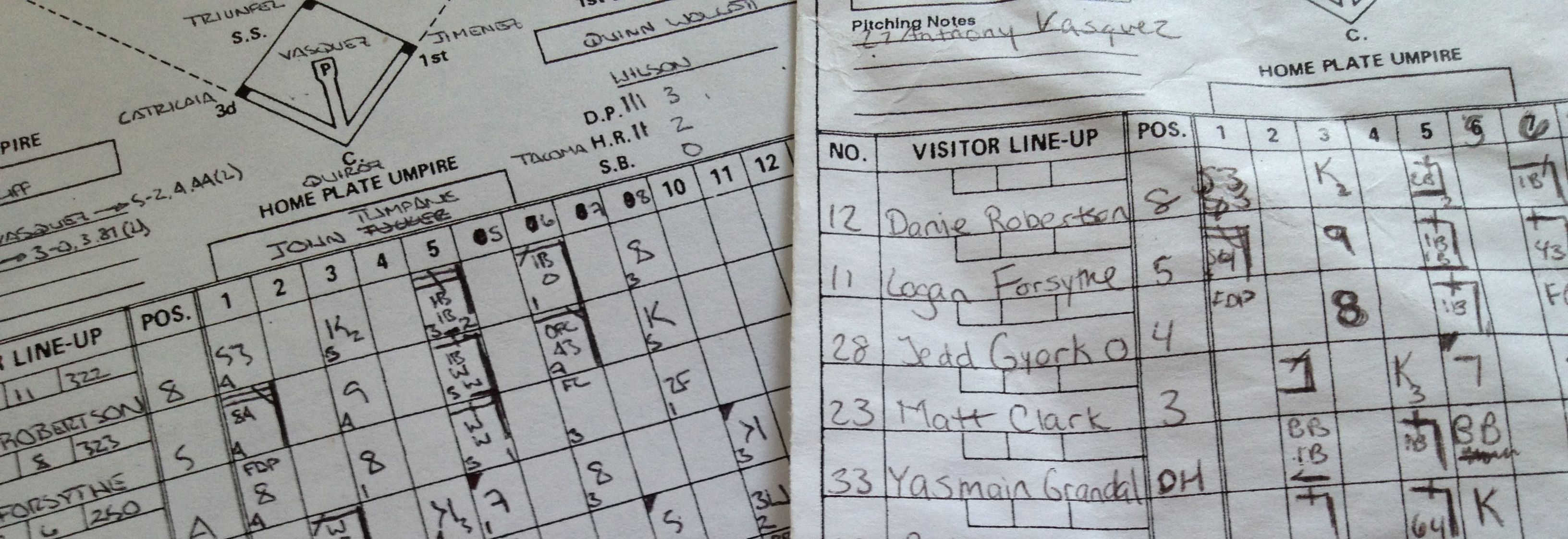

Tucson centerfielder Daniel Robertson walks to the plate to lead off the game and my nerves strike. I can’t remember what numbers and letters to use. I can’t remember how to put them together. Robertson grounds out to third and I scribble, an S, a 3, another S and a 4. Then I circle it. (What? What does that even mean? S3S4? That sounds like something out of Star Wars.)

(What else do you share with the woman you love, other than cramming microscopic shorthand on a sheet of paper for three hours?)

Then Tucson third baseman Logan Forsythe doubles to left and I mark that just like Matt showed me. (Two horizontal lines, a slash from the lower right to the upper left and a thick vertical line along the right side of the box to mark it as a hit. Makes perfect sense.) And then second baseman Jedd Gyorko does … something. I write IDP. And I mark an S and a 4 for Forsythe. And then the inning is finished. (Gyorko actually flies out into a double play. Mark that “FDP 43.” Again, makes perfect sense. Three up, three down.)

In the bottom of the first, Tuscon centerfielder Trayvon Robinson walks (“BB”), second baseman Luis Rodriguez walks (another “BB”) and rightfielder Carlos Peguero strikes out (“K”). Then third baseman Luis Simenez walks (still another “BB”) to load the bases, shortstop Carlos Triunfel singles to center, Robinson and Rodriguez score and I ask Matt what to write. (One thin horizontal line with a thin vertical line at the top of the middle of the box, another thick vertical line on the right side of the box and a “2” in the lower right corner to note his two RBI. Easy. … Wait. What is that on your scorecard?) After Robinson walked, I marked “BB” in the middle of his box. (Why? Why would you do that? You need to save room for what he might do on the bases.) Matt tries to explain something to me about small letters, but the Rainiers hit a pair of doubles, score three runs and fill up my entire column for the first inning.

Matt turns to me and says, “Welcome to scoring.” (I might have said that.)

None of this makes perfect sense.

♦ ♦ ♦

We sit in the cold, inning after inning, with a couple friends who live in Seattle. Matt talks with Stephen about bad baseball teams and scorecards. Stephen used to write for big newspapers and knows how to keep score, but never does anymore. Why bother when there are so many other things to do during a game, like eat a hot dog? Or drink a beer? Or talk with friends?

(Why bother? Are you really asking that question? We bother because keeping score helps you keep track of the game, it allows entry into the rhythms of nine innings, it connects you with a time before video boards, when keeping score was the only way to know whether this batter at the plate had accomplished anything at all. Without a card and at least some rudimentary marks in front of you, what unfolds on the field is just chaos.

None of this makes perfect sense.

I watched baseball for six years before I scored a game, and I only scored my first — a five-hour, 12-inning mess of a playoff game that required a second card ripped from the program my friend Jason sifted through earlier that afternoon — on the spur of the early October moment. I still have that card. And several books filled with games from the last 16 years. And lots of memories. That’s why we bother. That’s why I bother.)

I start to create memories in the fourth. That also happens to be the inning when a look at my card would make anybody think the basic rules of baseball have been thrown away for a night. In the top of the inning, Tucson leftfielder Cody Decker singles to center, then, inexplicably, returns to the box and grounds out to short. (He really does single, but he is retired on the front end of a 6-4-3 double play.) In the bottom of the inning, Robinson might have batted, or he might have just disappeared in a scratch of ink. All that remains as proof of his work in that inning is a black box. (He really does bat. He flies out to left, his fourth plate appearance in four innings and the last batter of a long inning.)

When I look at the scoreboard, I know the Rainiers lead the Padres, 13-2, a ridiculous score.

When I look on my card, I can only guess.

♦ ♦ ♦

As the sun goes down and the cold air stings my fingers, I finally start to find my rhythm.

Naturally, the teams begin to lose theirs.

The Padres sent 10 men to the plate and scored four runs in the top of the fifth (which provided Carolyn with all sorts of trouble after she attempted to squeeze both of Tucson rightfielder Jonathan Roof’s at-bats into the same box, then later started the column for the sixth inning in the same column where she finished the fifth), and then both teams just stopped scoring ... and hitting ... and reaching base much at all.

(Without a card and at least some rudimentary marks in front of you, what unfolds on the field is just chaos.)

Over the last four innings, both teams collected three hits. Neither team scored. My card started to look pretty accurate. (This is actually true.) Any rough patches my card needed to endure during those early innings were now close to over. I figured out how to mark wild pitches (nothing more than “WP,” of course).

I even learned how to mark a called strikeout — a backward “K.” Always did want to practice writing my letters backward. (Surprisingly helpful at sobriety checkpoints ... which Carolyn might need if an officer looked at the early innings of her card.)

Tacoma righty Chance Ruffin retired the Tucson side in the top of the ninth on a called strikeout, a grounder to first, a walk and a fly out to right — or a backwards “K,” a “3U,” a “BB” and a “9” for those of you scoring at home (which makes no sense, because this is a feature story and not a baseball game). We walked out of the stadium cold and wet. I walked out with my first finished (more or less) score card.

♦ ♦ ♦

Matt holds his scorecards to an incredibly high standard. His horizontal lines could be marked with a ruler, his vertical lines are parallel to every little rectangle, his letters and numbers are as precise as those on an engineer’s draft sheet. His cards have developed over 16 years. (They are beautiful). They are ridiculous.

My card is far from perfect. Lines are crooked, some boxes are full of loopy letters, others are crossed out and filled with Xs. It looks more like a scorecard for bowling than baseball.

My card is far from perfect. Lines are crooked, some boxes are full of loopy letters, others are crossed out and filled with Xs. It looks more like a scorecard for bowling than baseball.

Both cards tell the same story, though. And both cards help us keep memories of a night that started with a rain delay, ended after 11 p.m. and will be in our minds for a long time as the game I learned to keep score. (Carolyn really did improve, even over nine innings. Proud of her.)

I might never score another game, but for one night, I gained a deeper appreciation for the game and its details. I felt like I understood it all a little more.

(And I finally learned that, so long as you have a card and a pencil — or a pen — in front of you, there is no wrong way to score a game. Call it tolerance, progress.

For one night, I looked at something that requires obsession and compulsion, and let go.)

Carolyn@AMinorLeagueSeason ♦ Matt@AMinorLeagueSeason.com ♦ @CarolynLaWell ♦ @MattLaWell ♦ @AMinorLgSeason

Want to read stories about the other teams on our schedule? Click here and scroll to the calendar.