BY MATT LaWELL

MONTGOMERY, Alabama | Before he signed a contract that might pay him tens of millions of dollars over much of the next decade, before he shut out the Texas Rangers in the first game of the playoffs or struck out nearly a dozen New York Yankees over five innings in the Bronx, even before he dazzled during his short stint in North Carolina, Matt Moore walked onto a mound in Mobile and cut through the Alabama humidity with curveballs and changeups and ridiculous heaters.

For one glorious night, he gave up no runs and no hits.

He allowed no mistakes.

He afforded no hope.

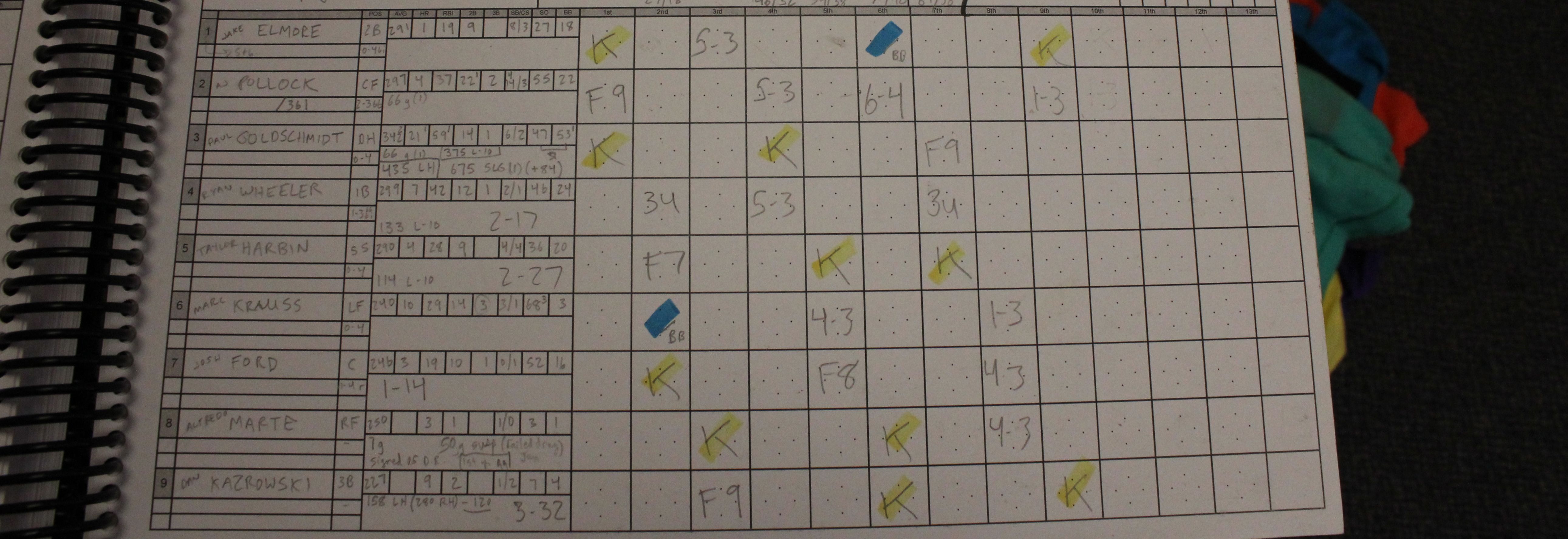

On June 16, 2011, two nights before he turned 22, less than three months before Tampa Bay called him up from Durham and dropped him in the middle of an incredible playoff push, Moore pitched in front of maybe a thousand fans in a park near the Gulf of Mexico and, still a Montgomery Biscuit, no-hit the Mobile BayBears. He walked two, struck out 11, fired 76 strikes among his 106 pitches. By all accounts, his control never wavered. He attacked hitters early, rarely nibbled corners, pitched in the strike zone and not out in the margins. The start was just one of 29 he made across three levels last season, one of the few without any video evidence of its existence, only one photographer roaming Hank Aaron Stadium on a Thursday night.

In the big picture, the no-hitter means so little. Moore had dominated the Southern League — and would later baffle International League hitters — and he appeared headed for another promotion, the next Rays pitcher in line to climb the ladder toward Tropicana Field. This night would neither make nor break what the Tampa brass thought of him. Besides, no-hitters down in the minors are so often forgotten over time, faded more every season, footnotes to successes or failures in the Majors.

Who remembers what pitchers accomplish in the minors at 21, 23, 25 years old? Who remembers even what they themselves accomplish at that age?

“It happened so fast, you couldn’t appreciate how or why it was happening,” Moore says. “I still don’t know why it happened.”

“Fastball, swing and a miss, strike three. Good tail to it off the outside edge, and the BayBears with their first look at Matt Moore, a three-pitch strikeout against Jake Elmore.” — Montgomery Biscuits radio broadcaster Joe Davis

Joe Davis, for one, still remembers what Matt Moore accomplished that night.

He remembers he was upstairs, behind a microphone, 66 games into his second season as the radio voice of the Biscuits. He remembers he was the youngest broadcaster in Double-A when the team hired him prior to the 2010 season and that he was still one of the younger radio play-by-play broadcasters in the country then, less than two years older than Moore. And he remembers before the game, when the Mobile radio broadcaster, Wayne Randazzo, slid open the window that separated their booths and told him Moore was going to throw a no-hitter.

He remembers that he laughed for a second or two.

“Moore struck out Paul Goldschmidt to end the first inning, and he made him look terrible,” Davis says. “A changeup down and away, and it took like nine pitches to finish the first inning. Wayne and I just kind of looked at each other through the glass. Wayne was nodding his head.”

Davis played four seasons of college football and has called nearly three full seasons of minor league baseball. He has been around sports in some capacity almost all of his life. He has a good idea about what makes a big moment. And he started to think during the early innings of that game that he might be watching a big moment.

Moore had started to develop his changeup more during the early months of the season. He wanted to develop another quality pitch in addition to his fastball, which normally sits around 94 mph and tops out around what he says is 99 mph, and his curveball, which breaks later and keeps batters guessing more often. The changeup would add more deception and make batters vary the speeds of their swings.

And during his warmup in the bullpen during the minutes before the first inning, Moore’s changeup was perhaps as good as it had ever been. His pitching coach, Bill Moloney, saw it. So did his catcher, Nevin Ashley.

And so did Moore. Davis might not have been the only one thinking they might be watching a big moment.

“One-one, another fastball, skied to center, a soaring fly ball that sends Shelby back a couple of steps. Waiting underneath it, puts it away, and Matt Moore has thrown five hitless innings.” — Davis

Matt Moore still remembers what he did that night, too. He’s up with Tampa Bay now, the most heralded rookie pitcher in the Majors, the owner of a contract worth at least $14 million and, potentially, close to $40 million between now and the end of the 2019 season. That no-hitter isn’t on his mind much, not with the Yankees in front of him, the Boston Red Sox, the rest of the division and the league. But he still remembers. “I couldn’t tell you what was going on,” he says. “I could just repeat the process of what I was doing every pitch.”

How did he improve so much so quickly? During his first four seasons in the minors — in the Appalachian League, the South Atlantic League, the Florida State League — he won 16 games and lost 18. He was always healthy, never on the disabled list, but averaged only about five innings per start and finished none of his 67 starts. He allowed a surprisingly low number of hits, a little more than six per nine innings, and his ERA to that point was just 2.97, but he also walked nearly a batter every other inning.

He was a good starting pitcher, capable of striking out any batter at any time, but not a great one. He was a good prospect, but not one of the top two or three in all of baseball.

How did he make that jump?

Moore was never fat or lazy, he just never focused on every last detail. After his 2010 season with the Charlotte Stone Crabs, he headed back West, in and around New Mexico, where he was raised and pitched in high school. He started to work out at least two hours every day in Tempe, Arizona, with a sustained target heart rate between 120 and 180. Those workouts lasted about two months, until New Year’s. He shied away from longer distance runs — great for cardiovascular and conditioning, just not for the short bursts he used on the mound — in favor of intervals. He paid more attention to his nutrition, down to planning meals days or a week in advance, even opting out of tortilla shells at Chipotle and substituting double meat and double beans.

By the time the 2011 season started, he still weighed 201 pounds. His body fat, however, had dropped from what he says was 14 percent to 9.5 percent.

The results on the mound were close to immediate. On opening night, Moore held the Birmingham Barons to a run on two hits over five innings, striking out seven without walking a batter. Six days later, the Tennessee Smokies knocked him around for six runs on 10 hits over 4 1-3 innings; still, Moore struck out four and didn’t walk a batter. That was his last poor start in the Southern League. Over his next 11 starts going into that night at Mobile, he struck out 80 and walked 21 over 60 1-3 innings, averaging nearly six innings per start with a 2.09 ERA and a 1.04 WHIP. He allowed more than four hits twice. He allowed more than two earned runs once. He had never pitched better.

“I really try not to let it go to my head or think about it too much, because there are still things I need to work on,” Moore says later on during the season, after his call to Durham and before his debut in Tampa Bay. “I don’t have this thing halfway figured out.”

“Lefty on righty, the kick and another two-two. Curveball, big bouncer over the mound, charging O’Malley, takes it with the bare hand and THROWS TO FIRST IN TIME! Shawn O’Malley barehands an in-between hop, whips a one-hopper to first that Wrigley spikes out of the dirt! And we go to the ninth inning, 5-0 Biscuits, Matt Moore with eight no-hit frames against the BayBears.” — Davis

Every no-hitter seems to have one play that saves it from becoming just another very good pitching performance. These blur into the highlights of the day, the montage of memory, and they also drift quickly into the background. More people remember Don Larsen, Kenny Rogers and Mark Buehrle than they do Gil McDougald, Rusty Greer and DeWayne Wise.

More people will remember Matt Moore than they do Shawn O’Malley.

The no-hitter itself lasted a long time, especially considering there were no television breaks, no weather delays, nothing at all to drag it close to three hours. Montgomery did score eight runs thanks to nine hits, seven walks and a hit batter, which stretched the game longer than might have otherwise been expected. A trio of Mobile pitchers combined to throw 179 pitches — 73 more than Moore.

Moore retired the side in order in the first, then walked leftfielder Marc Krauss with two outs in the second. The perfect game was gone, if anybody at Hank Aaron Stadium was thinking about it by that point. Then Moore retired a dozen in a row before walking second baseman Jacob Elmore with two outs in the sixth.

That was the last time Mobile mustered anything that actually showed up in the box score.

The only real scare came with two outs in the bottom of the eighth, with Moore cruising and Mobile rightfielder Alfredo Marte at the plate. Marte was batting .222 against Southern League pitching to that point. He almost bumped up his average.

Marte hit a 2-2 pitch hard into the grass. The ball bounced high over Moore’s head and appeared headed for a spot between Moore on the mound and O’Malley at second base. O’Malley remembers that he needed to “fly” toward the ball. He grabbed it with his bare right hand, never closing his fingers around the stitches, then pushed it toward first baseman Henry Wrigley. The ball hit the dirt. Wrigley scooped it. First base umpire Will Thornewell raised his right arm.

The inning was over. After the Biscuits scored three more runs in the top of the ninth and Moore retired three more batters in the bottom of the inning, so was the game.

“Infield plays back, the outfield shaded to right, and from the third-base side of the rubber, Moore strides home with the first one. It’s a fastball bounced back to the mound. Moore’s got it. Throws to first! In time! And Matt Moore has thrown the first no-hitter in Biscuits history!” — Davis

No-hitters have been around almost as long as the sport itself. Joe Borden pitched the first recorded no-hitter, back in 1875 for the Philadelphia White Stockings. George Bradley pitched one for the St. Louis Brown Stockings less than a year later, the first recognized by the Majors. Larry Corcoran pitched no-hitters for the Chicago White Stockings in 1880 and 1882 to become the first pitcher to throw a pair, then added another one in 1884 to become the first to throw three. Noodles Hahn threw the first in the 20th century, a year and three days before a considerably more memorable name — Christy Mathewson — threw the second of the last century. Not common knowledge, but easy enough to ferret out of the right sources. Look for a few minutes, and all this information is readily available in online databases and in old record books. Baseball is about fun facts, odd moments, things you’ve never seen before. The unforgettable.

We know that Bumpus Jones was the first pitcher to throw a no-hitter in his Major League debut, and that Fred Toney and Hippo Vaughn were the first to throw nine no-hit innings against each other. We know that Babe Ruth and Ernie Shore were the first to throw a combined no-hitter, though Ruth was ejected before he retired a single batter and Shore pitched all nine innings. We know that Sam Jones was the first to throw a no-hitter without striking out a batter (and that decades later, another Sam Jones threw a no-hitter and struck out six). We know that Johnny Vander Meer was the first to throw no-hitters in consecutive starts, that Bob Feller was the first to throw an opening day no-hitter, that Bob and Ken Forsch were the first brothers to each throw a no-hitter, that Sandy Koufax was the first to pitch four no-hitters, that Jason Varitek was the first to catch four no-hitters.

There is no similar information for minor league no-hitters.

They are not unforgettable.

We know when Moore pitched his no-hitter, of course, and where, and against what team. Thanks to MLB Advanced Media and its GameDay program, used now at just about every Double-A, Triple-A and Major League game, we know his pitch count by inning on that June night — 13 in the first, 14 in the second, 12 in the third, then 7, 8, 16, 11, 14 and 11 the rest of the way in a remarkably efficient performance.

But after Moore walked off the mound, his cap askew, his silver jersey untucked, no one added his name to any sort of log. Individual leagues keep their own records. There is no definitive list. The Southern League, for instance, counts 76 no-hitters in his history, including 35 of less than nine innings and eight more that were combined efforts. What happened in these games? Are there box scores in the old newspapers of small towns? If not, who remembers? What is the legacy of the games?

Major League records are made to be broken. Minor league records are made to be written down, set aside and ultimately forgotten in the fog of modern history. Somebody will always remember the no-hitters hurled in small stadiums before crowds that can be counted by hand, because somebody has to. The fans who paid attention and stayed until the end, the ushers who thanked everybody for coming, maybe a concessions stand worker who was able to close an inning early and catch the end. The scorekeepers, the radio broadcasters, the umpires. The pitcher, of course, and his teammates, their opponents.

For a while, Moore’s no-hitter will remain alive in print and audio and memory. Too soon, it will exist only in the margins.

Matt@AMinorLeagueSeason.com ♦ @MattLaWell ♦ @AMinorLgSeason

Want to read stories about the other teams on our schedule? Click here and scroll to the calendar.